Olive Brittan – Beekeeper to the King of Libya by Xuejiao Huang

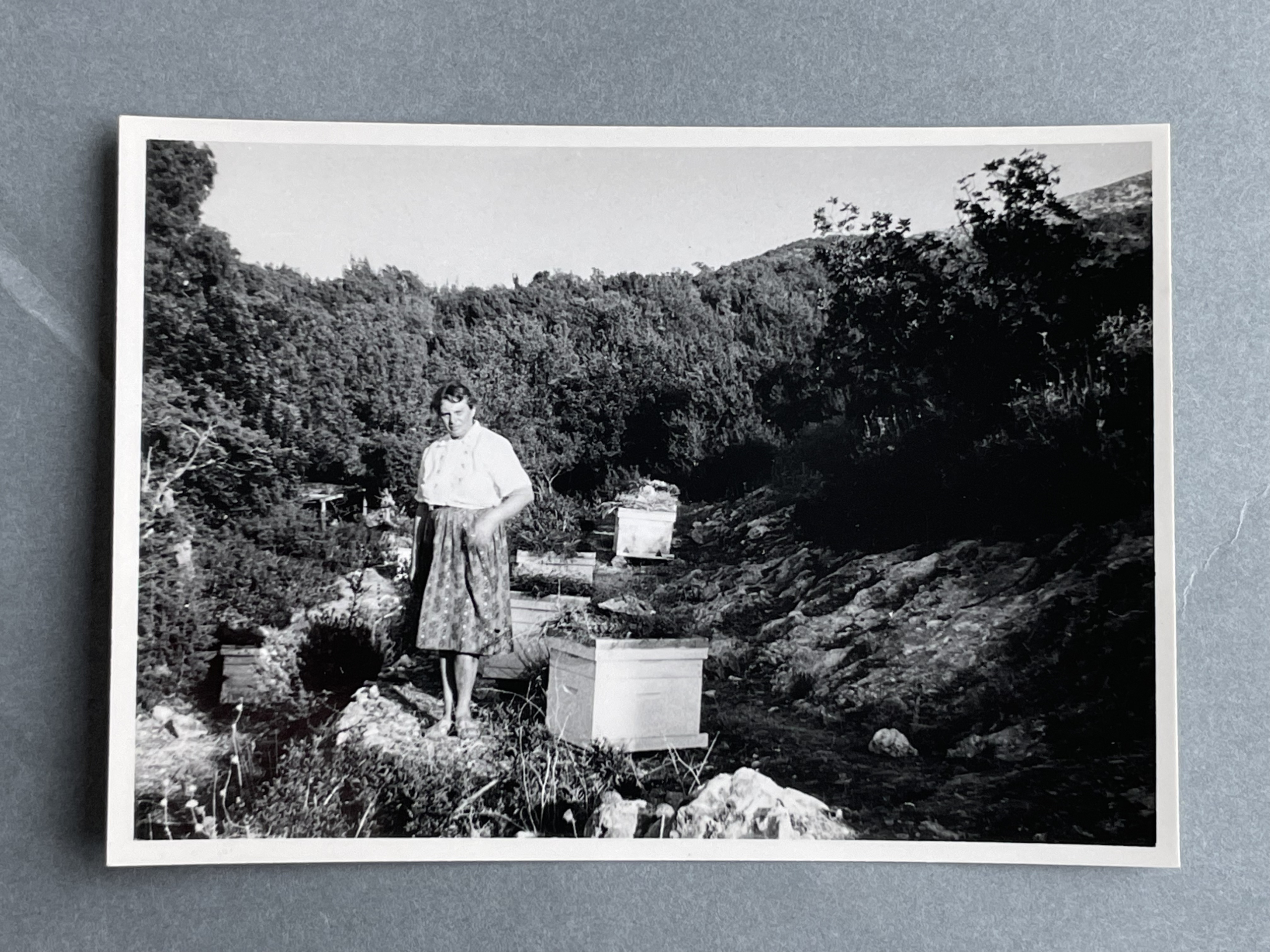

Image 1: L-R: Audrey Webb, Olive Brittan and Martyn Webb (1963). BILNAS/D15/1/5/5, ‘Libya’ (1963), Martyn and Audrey Webb Papers on Cyrenaica. © BILNAS

While working at the BILNAS Archive on the Martyn and Audrey Webb Papers on Cyrenaica, I came across two letters included in the file Cyrenaican Expeditions of the University of Manchester 1955–57. Both were signed by Miss Olive Brittan, ‘Beekeeper of the Kingdom of Libya’. These letters, fragile and deeply personal, describe a woman trying to hold together a project in difficult circumstances.

Image 2: BILNAS/D15/7/2 , ‘Cyrenaican Expeditions of the University of Manchester 1955-57’ (1959), Martyn and Audrey Webb Papers on Cyrenaica. © BILNAS

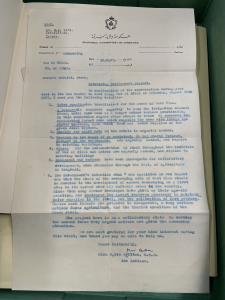

In her correspondence to Martyn Webb, Brittan explained that her house at Ras el Hilal had been damaged by an earthquake and could not be repaired for lack of funds (See image 3). She wrote of staff shortages and the difficulty of keeping her work going, and above all, she warned that without protection, the native bees of the Green Jebel forests would not survive the winter. She mentioned the need for night shifts, linked to the unusual nocturnal foraging habits of Libyan bees.

Image 3: BILNAS/D15/7/2, ‘Cyrenaican Expeditions of the University of Manchester 1955-57’ (1959), Martyn and Audrey Webb Papers on Cyrenaica. © BILNAS

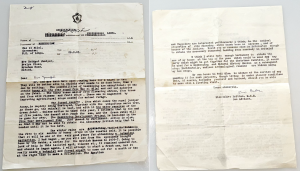

One letter records that Martyn and Audrey Webb had visited her on 24 August, 1963, listened to her concerns, and promised to help. Another was addressed to Mrs. Bridget Juniper (See image 4), showing that Brittan was also seeking expert advice and financial help from Britain.

Images 4: BILNAS/D15/7/2 ‘Cyrenaican Expeditions of the University of Manchester 1955-57’ (1959), Martyn and Audrey Webb Papers on Cyrenaica. © BILNAS

These letters capture Brittan’s voice at a moment of difficulty. They also invite us to look back into her earlier life and the wider project that first brought her to Libya. Brittan’s earlier experiences had already been remarkable. From the 1940s, she was based in the Middle East, first as a Red Cross worker assisting Yugoslav and other wartime refugees in Egypt, and later as a social worker during the British Mandate in Palestine. These years gave her both the linguistic ability (she became fluent in Arabic) and the personal resilience that later enabled her to live independently in rural Cyrenaica.

Image 5: Olive Brittan with some RAF officers stationed at El Adem (1962/63), photography by Albert Webb, Propolis (2007).

In 1952 she came to Cyrenaica with Lieutenant Colonel E. G. Evans, who later in 1956 became Military Administrator and District Commissioner for Benghazi. Together they began establishing an apiary at Wadi Glaa, introducing modern Langstroth hives imported from Benghazi. This effort was not an isolated venture, it was closely tied to wider international technical assistance programmes that followed Libyan independence. In 1950, the United Nations had argued that technical assistance for Libya was essential. In 1951, Britain, France, and the United States signed an agreement in London outlining technical support, including American commitments under the newly created Libyan-American Technical Assistance Service (LATAS). Earlier, in 1949, the United States had launched the ‘Point Four’ programme to provide funds and expertise to developing nations, especially those emerging from colonial rule. Under this programme, Libya received an allocation of $150,000 for agricultural education and survey work.

In practice, however, LATAS supplied hives, it did not provide the training that was supposed to accompany them. The original plan had been to demonstrate modern beekeeping and teach local people how to manage bees effectively, but the training element was never fully realised. When Evans left in 1956 for government duties in Benghazi, the responsibility for continuing the work fell to Brittan. She installed the hives, stocked them with local bees, and trained local workers to care for them.

Image 6: BILNAS/D41/3/11/9/30, ‘Mrs Brittan with beehives’ (1910-1979), Olwen Brogan Papers. © BILNAS

Brittan was not an amateur. She was a member of the International Bee Research Association and held the expert certificate of the British Beekeepers Association. In her letter to Web, she noted the government’s original intention had been to convert all of Wadi Glaa into a model of modern apiculture, with the aim of extending reform nationwide if it succeeded. By the early 1960s, however, that ambition had contracted to her own efforts in Ras el Hilal, where she faced earthquake damage, staff shortages, and environmental threats.

Image 7: BILNAS/D15/3/2 Olive Brittan’s residence at Ras el Hilal (1963), Martyn and Audrey Webb Papers on Cyrenaica. © BILNAS

Her residence at Ras el Hilal became the centre of her work. The house had once been used as a German officers’ convalescent home during the Second World War, and murals painted by soldiers still decorated its walls. From here she managed “bee hill,” where hives were set in caves and terraces above the village. By the mid-1960s, she was maintaining around 100 hives, producing up to twenty types of honey depending on the season, including rosemary, thyme, and above all juniper.

All juniper honey was supplied to King Idris I, giving rise to its name “Royal Honey.” Her work attracted wider attention only occasionally. In 1965, the BBC Tonight programme featured Brittan in an interview with Fyfe Robertson, in which he introduced her to viewers as ‘the King’s Beekeeper’. She explained the importance of preserving local bees, the role of pollination in agriculture, and the necessity of leaving honey for the bees themselves. The programme remains one of the only surviving moving images of Brittan.

The archive also shows her role in assisting visiting expeditions. The 1961 Oxford University Expedition to Cyrenaica thanked her in its report. Geologist Dudley R. Seifert later recalled being based in her house while carrying out fieldwork. He described her as a gracious but determined host, remembered her teaching him about the nine seasonal phases of honey, and recounted being chased indoors by angry bees while she worked with combs.

Image 8: BILNAS/D15/6/2/2, ‘Oxford University Exploration Club Bulletin, No 11’ (1964), Martyn and Audrey Webb Papers on Cyrenaica. © BILNAS

In 1963, the Webbs managed to visit Ras el Hilal and met Olive Brittan. Photographs taken by Nicholas Bevan, an undergraduate student, show Brittan with the Webbs and several local people, probably workers. The Sherborne School Expedition of 1965 recorded further details. By then the wider farm, which had once included poultry and dairy, had declined, but the apiary remained active. The students described “Bee Hill” with its hives, the taste of honey they considered the finest they had ever had, and the hospitality extended by Brittan.

They also wrote about her employee, local Sheikh Sherif el Moghtadi Ferkesh, a former member of Popski’s Private Army, who assisted visitors with both practical and medical needs.

Image 9: L-R: Three unidentified workers, possibly local Sheikh Sherif el Moghtadi Ferkesh, Olive Brittan and Audrey Webb (1963) BILNAS/D15/1/5/5, ‘Libya’ (1963), Martyn and Audrey Webb Papers on Cyrenaica. © BILNASOther memories add further texture. One RAF officer recalled that after the Libyan revolution in September 1969, a unit of Royal Irish Rangers was sent to escort Brittan out of Libya, though she was reluctant to leave. Another remembered that her house was often completely dark at night, as she could not afford oil for her lamps. Volunteer teacher Guy Ogden recalled being visited by Brittan in a hospital in Derna in 1967, when she brought him honey. Some visitors even remembered camping on her floor when stranded without light. These informal stories align with the difficulties she described in her letters: shortages, resilience, and the fragile support of personal networks.

Image 10: RHS: Olive Brittan and Audrey Webb (1963). BILNAS/D15/1/5/5, ‘Libya’ (1963), Martyn and Audrey Webb Papers on Cyrenaica. © BILNAS

Brittan did receive some formal recognition. In 1959, she was created a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE). This was a rare distinction for a British woman living independently in Libya. Beyond this, however, her public record is slight.

Her departure from Libya came at a time of great political change. After the revolution in 1969, foreign specialists were required to leave. Sir Peter Wakefield, then Consul-General, recalled that Brittan insisted on a ceremonial farewell. She led him and the military mission’s colonel to Bee Hill, unfurled the Union Flag for a final salute, and then folded it away. She returned safely to Britain in 1970. The apiary at Ras el Hilal, once intended as a model for national reform, disappeared from view.

Much of the surviving evidence about Olive Brittan focuses on her work, her bees, her house, her visitors and friends. The broader story of her life remains largely unrecorded. She had lived in the Middle East since the 1940s, far from Britain and her family. To choose such a life in that period, and to sustain it alone for nearly two decades in rural Cyrenaica (1952-1970) was in itself remarkable.

Image 11: BILNAS/D15/3/2, L-R Olive Brittan, Martyn and Andrey Webb enjoying a Libyan feast (1963), Martyn and Audrey Webb Papers on Cyrenaica. © BILNASBecause her story was never formally written, much of it has been hidden. Apart from the BBC interview, almost no moving images or films of her survive. Only through scattered traces, a handful of letters, expedition reports, photographs, and recollections, can we begin to reconstruct her life. Recently, I was able to identify one of the very few clear photographs of her, perhaps, one of the last that still exists. Telling her story, therefore, is not just about the history of beekeeping in Libya, it’s about recovering the presence of a woman whose choices defied the expectations of her time and whose contribution has slipped into obscurity. Why did she move from the Red Cross service in wartime to become a beekeeping expert? What made the Libyan government appoint her to this role? These questions remain unanswered, and so the research continues.

For now, the fragments preserved in the BILNAS archive ensure that Olive Brittan is no longer entirely hidden but recognised as part of Libya and Britain’s shared history.

If anyone has any information about Olive Brittan, please contact me at Xuejiao Huang ([email protected]) or Anne Marie Williamson ([email protected])

____

Bibliography

Anon., Supplement to the London Gazette, 1 January 1959, (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1959). Available at: https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/41589/supplement/21/data.pdf (Accessed: 3 September 2025).

BBC Archive, 1965: Beekeeping for The King | Tonight | Weird and Wonderful | BBC Archive (1965). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yNdoqrbU1XA (Accessed: 3 September 2025).

Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, Treaty Series No. 55 (1951): Technical Assistance for Libya, (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 15 June 1951). Available at: https://treaties.fcdo.gov.uk/data/Library2/pdf/1951-TS0055.pdf (Accessed: 3 September 2025).

Hassall, Rachel, ‘1965 Western Desert Expedition’, The Old Shirburnian Society (28 July 2025). Available at: https://oldshirburnian.org.uk/school-archives-news/1965-western-desert-expedition/ (Accessed: 3 September 2025).

Karayam, Hasan, Libyan-American Relations, 1951–1959: The Decade of Weakness, Master’s thesis, Middle Tennessee State University, (December 2018). Available at: https://jewlscholar.mtsu.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/da3e14d0-9d6f-441e-b28b-64dcb31a622c/content (Accessed: 3 September 2025).

Pauly Paul, ‘Cyrenaican bees: nocturnal foraging?’, Beekeeping & Apiculture Forum (03 March 2024). Available at: https://beekeepingforum.co.uk/threads/cyrenaican-bees-nocturnal-foraging.56524/ (Accessed: 3 September 2025).

Showler, Karl. ‘Beekeeper to the King of Libya: Olive Brittan’, Bee World, 88(4), pp.86–90, June 2011. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/0005772X.2011.11417403 (Accessed: 3 September 2025).

Turlough, ‘Miss Olive Brittan, Libya’s Last Queen Bee’, Propolis, 5 February 2005. Available at: https://turlough.blogspot.com/2005/02/miss-olive-brittan-libyas-last-queen.html (Accessed: 3 September 2025).

– ‘The Last Queen Bee of Libya’, Propolis, 20 December 2007. Available at: http://turlough.blogspot.com/2007/12/last-queen-bee-of-libya.html (Accessed: 3 September 2025).

Venning, P.D.R., Sherborne School Expedition to the Western Desert Report 1965: July 26 th – September 8 th , The Old Shirburnian Society (26 July 2025). Available at: https://oldshirburnian.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Expedition-to-the-Western-Desert-Report-1965.pdf (Accessed: 3 September 2025).

United Nations General Assembly, Technical assistance for Libya after achievement of independence, UN. General Assembly (5th session,1950-1951, New York and Paris). Available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/209558 (Accessed: 3 September 2025).